Diffusion Policy Action Prediction

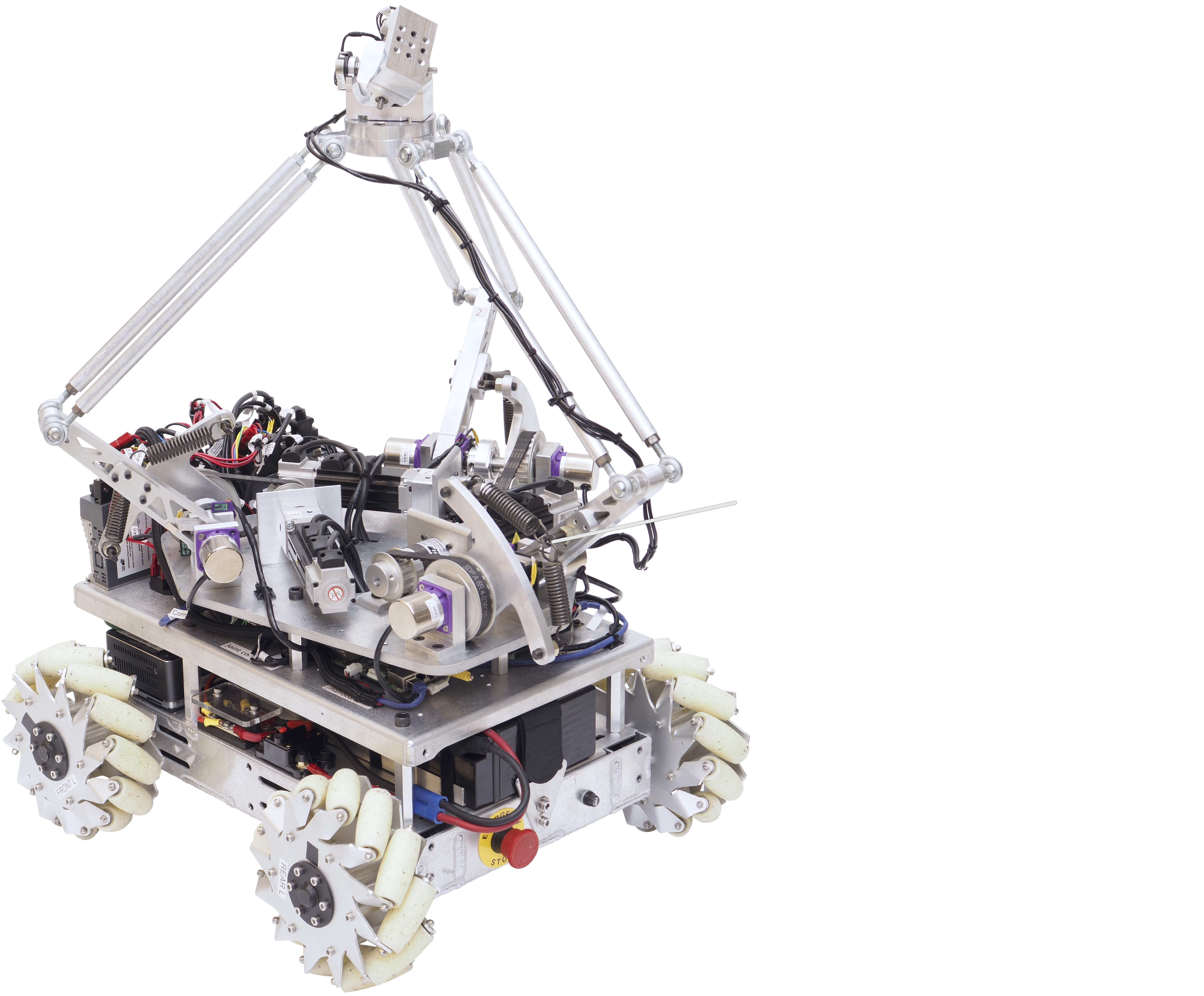

For my final project in Northwestern University’s MSR program, I worked with the unique omnidirectional mobile cobots, dubbed “omnid mocobots” or “omnids” for short. These collaborative robots were developed at Northwestern University by Elwin et al..

A portion of the project involved upgrading the omnids’ onboard systems, but the main goal of the project was to research novel ways to apply assistive action prediction using generative machine learning models. To do this, I explored diffusion policy, a method of generating robot actions using diffusion models.

Table of Contents

Assistive Action Prediction with the Omnids

Omnid System

The omnids were designed as an assistive tool to help human operators manipulate potentially large, delicate, flexible, and/or articulated payloads.

Each omnid consists of an omnidirectional mobile base and a series-elastic actuator driven Delta parallel manipulator on top. During the robot’s “float” mode, the manipulator is force-controlled to cancel the gravity of a payload and zero the contact force. The mobile base is commanded to center itself under the end-effector. This combination allows a human collaborator to easily guide the payload as it is carried by the omnids.

While they are also capable of autonomous action, the omnid team at Northwestern was particularly interested in exploring whether applying generative action prediction through models like diffusion policy could improve omnid performance in collaborative tasks.

Several potential system architectures were designed to explore this question. In each architecture, the generative model is used to produce an action, which is then executed by the system. The model in each architecture takes as input:

- End-effector X/Y/Z positions, velocities, and forces

- Gimbal X/Y/Z axis rotations

- Base twist (optional) from the float controller

- Image data (optional) from three cameras (overhead, horizontal, and onboard the omnid)

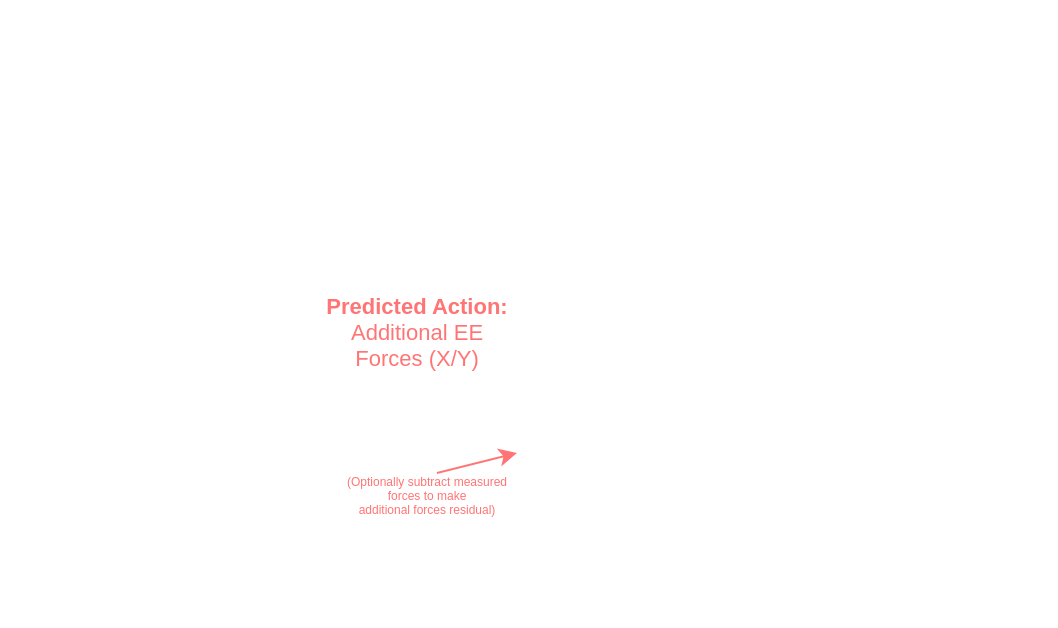

Force Prediction

The idea behind the force prediction is that if the model can predict the force applied by the human on the end-effector, the force controller can preemptively apply that force to assist the human. The predicted force can then be fed into the end-effector’s force controller as additional forces to apply to the end-effector. Optionally, the feedback end-effector force values can be subtracted from the prediction, so only the “residual” is fed into the force controller.

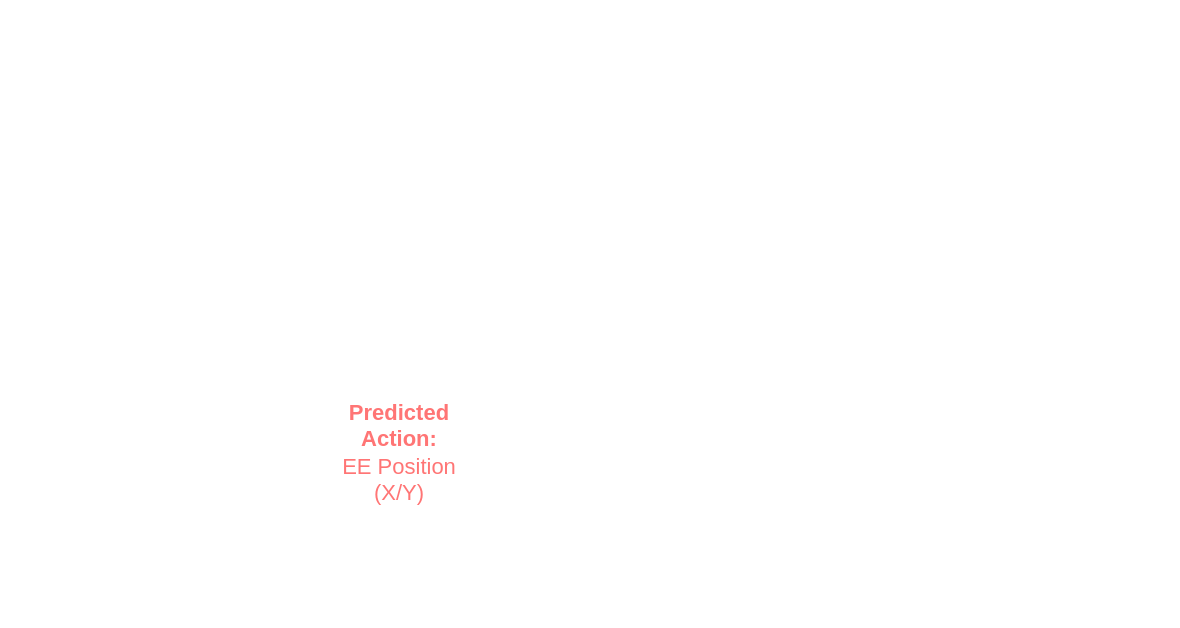

Position Prediction

Similarly, position prediction focuses on predicting the position of the end-effector (relative to its home position) and preemptively commanding the end-effector to that prediction via a position controller.

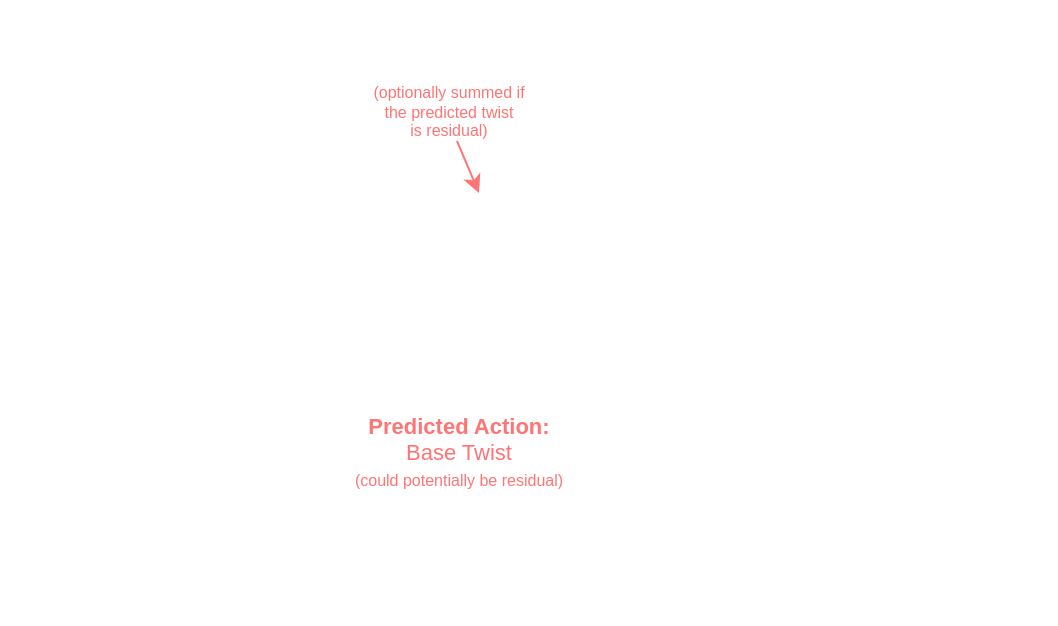

Base Twist Prediction

Finally, base twist prediction could either replace the float controller entirely or augment it with “residual” values. With this architecture, the base would follow a twist that anticipates the human’s actions.

Diffusion Policy

Diffusion policy was introduced in 2023. This policy applies diffusion models (a type of generative machine learning model) to the generation of robotic action sequences based on a dataset of human demonstrations. The action generation is conditioned on observations from the robot’s sensors, allowing the robot to consider its state and the state of the world around it while planning actions.

Expand for more details on diffusion models and how diffusion policy works.

What is a diffusion model?

Diffusion models were introduced in 2015 as a method of learning a model that can sample from highly complex probability distributions. The models used in this project are based on the denoising diffusion probabilistic model (DDPM), introduced in 2020.

A classic use of this type of model is image generation, where by training the model on a set of images, the model can then generate new images that approximate the input set.

This example is from a simple model I trained on the Caltech 101 Motorbikes dataset.

Expand for more details on image generation with diffusion models.

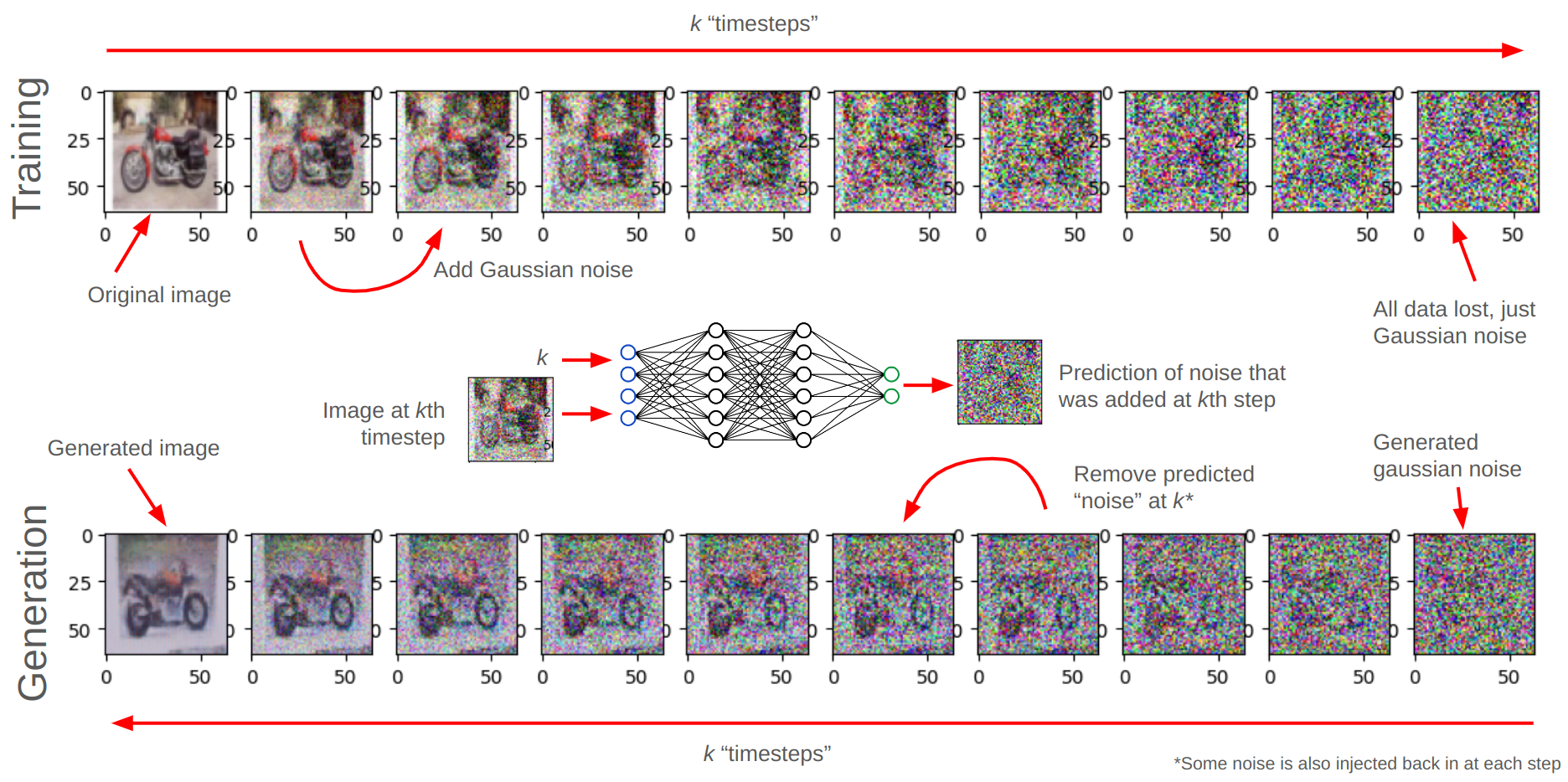

To do this, the process takes images from the input dataset and gradually introduces more and more Gaussian noise into them over k timesteps. Once enough of this noise is added, all of the original image data is lost, and all that remains is Gaussian noise. A neural network can subsequently be trained to take the diffusion timestep k and the noisy image at that timestep and “predict the noise” that was added to that image from the previous timestep.

Once the network has been trained, the process can then be reversed. An image consisting purely of random Gaussian noise can be generated. Then, over k timesteps, the model “predicts and removes the noise” iteratively, until a newly generated image is created.

Importantly, the model can also be conditioned on other inputs, such as a text prompt. At a high level, this is how many popular image generation models (such as Stable Diffusion and DALL-E 3) generate images from a text prompt.

The diffusion process for a small motorbike image.

What are diffusion models actually doing?

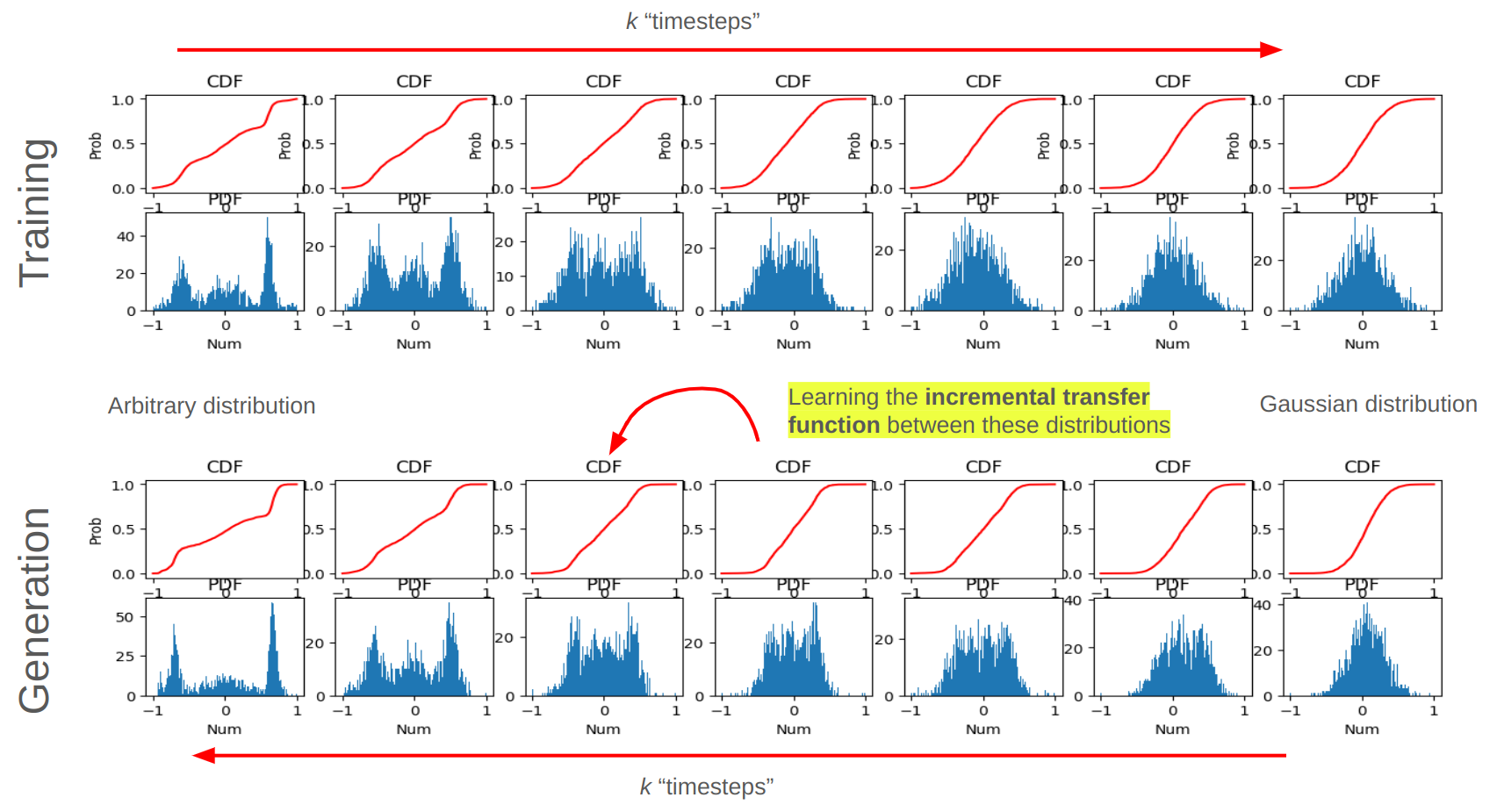

“Removing noise” from data (i.e. recovering information from nothing) is not possible - hence the popular description of the reverse diffusion process as “removing noise” to generate new images is not accurate. Instead the diffusion model is learning the transfer function between an arbitrary distribution and a Gaussian distribution. This is very useful, as it allows one to take a sample from a Gaussian distribution (which is simple to sample from) and transform it into a sample from an arbitrarily complex distribution of one’s choosing.

This example is from modifying the above image diffusion model and retraining it on an arbitrary multimodal 1D distribution.

How can diffusion models generate robot actions?

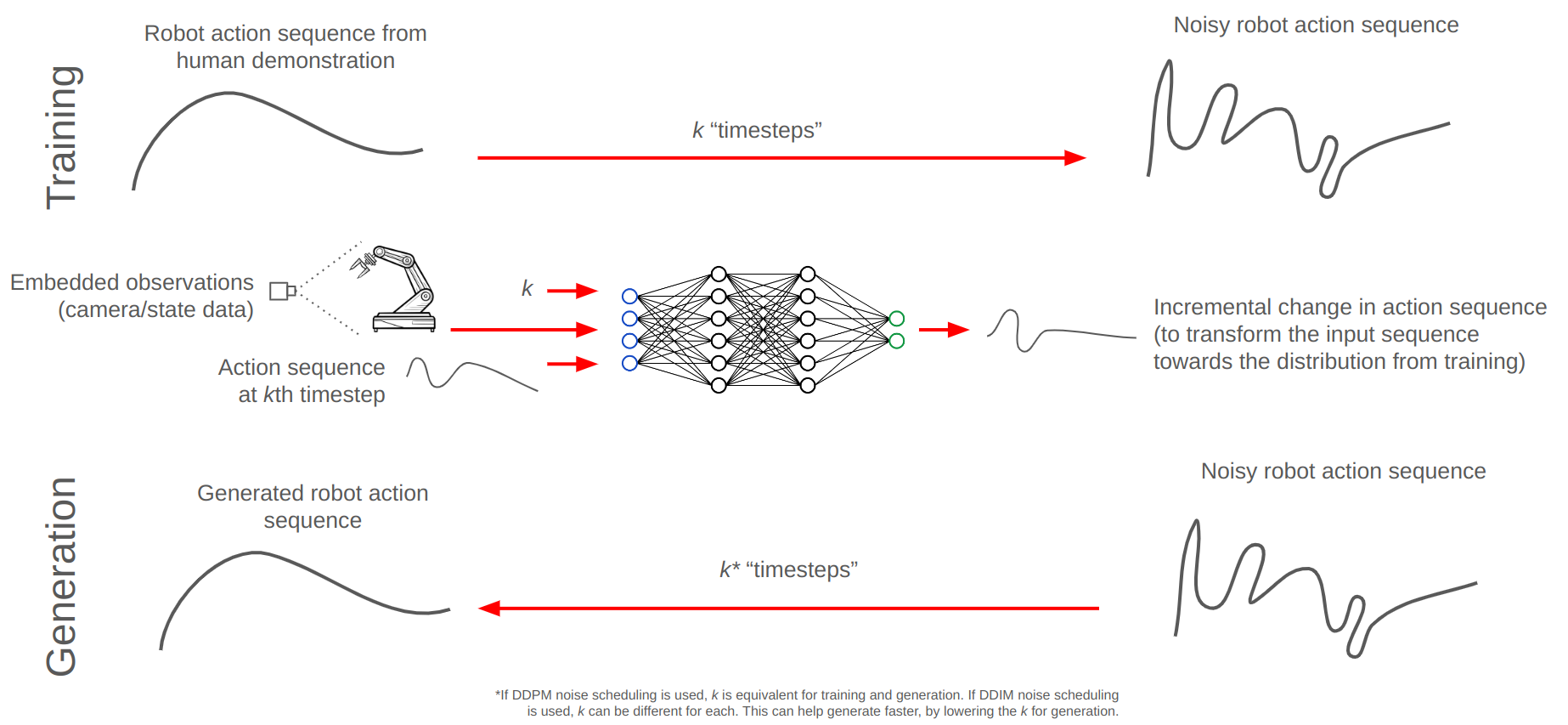

Diffusion policy applies diffusion models to the generation of action sequences based on a dataset of human demonstrations. Much like image generation models can condition their generation on text prompts, diffusion policy conditions the action sequence generation on the observations from the robot’s sensors - cameras, position/velocity/force feedback, and more.

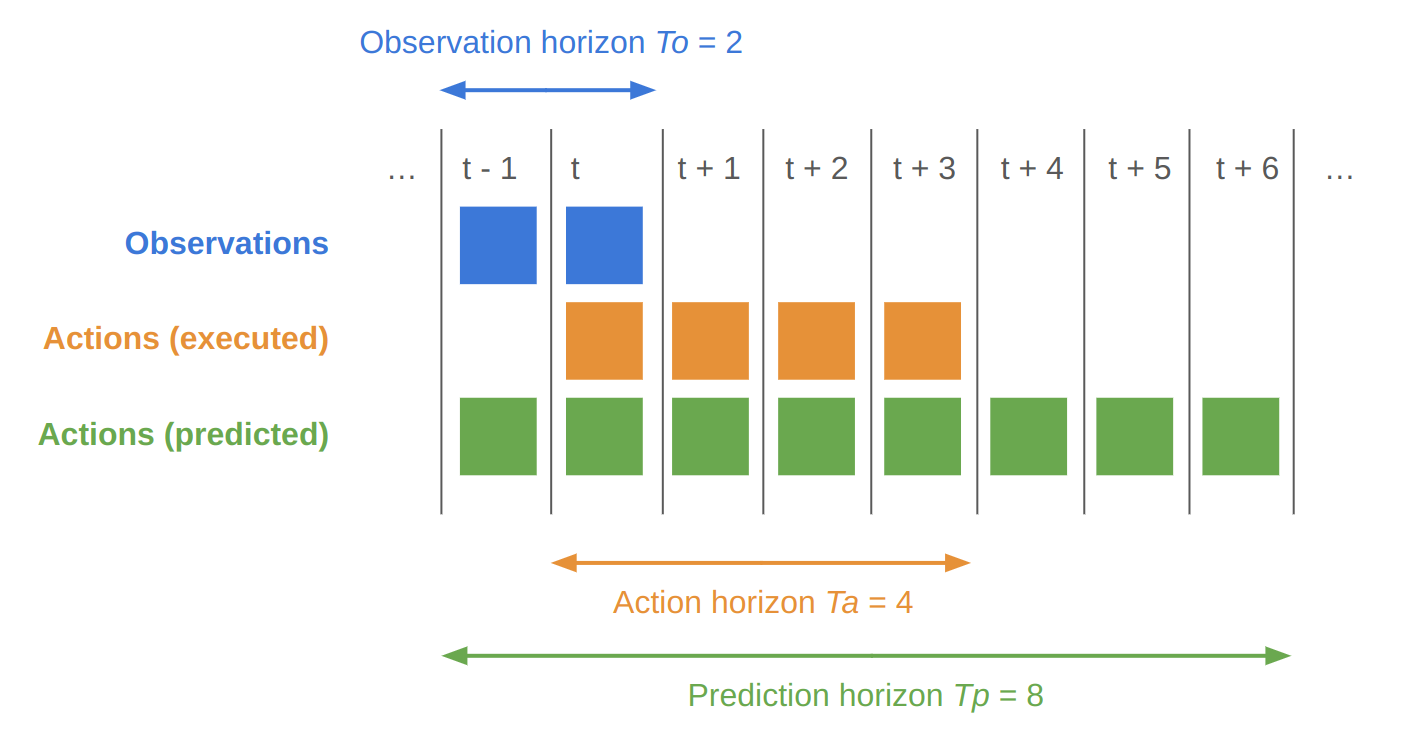

After predicting an action sequence across a prediction horizon (Tp) based on observations from an observation horizon (To), diffusion policy then performs receding horizon control. This means that only a subset action horizon (Ta) of actions is performed before the model performs a new prediction based on updated observations. Then the whole process repeats.

The advantage of using a diffusion model to plan robot actions like this is that, as mentioned above, diffusion models can sample from complex arbitrary distributions. Robot action sequence distributions are often complex and multimodal - there are often many ways a robot can accomplish a certain task, and diffusion policy handles those complexities gracefully.

Machine Learning Pipeline

In order to test the above architectures, a pipeline needed to be created with infrastructure for collecting data, training, and testing.

Data Collection

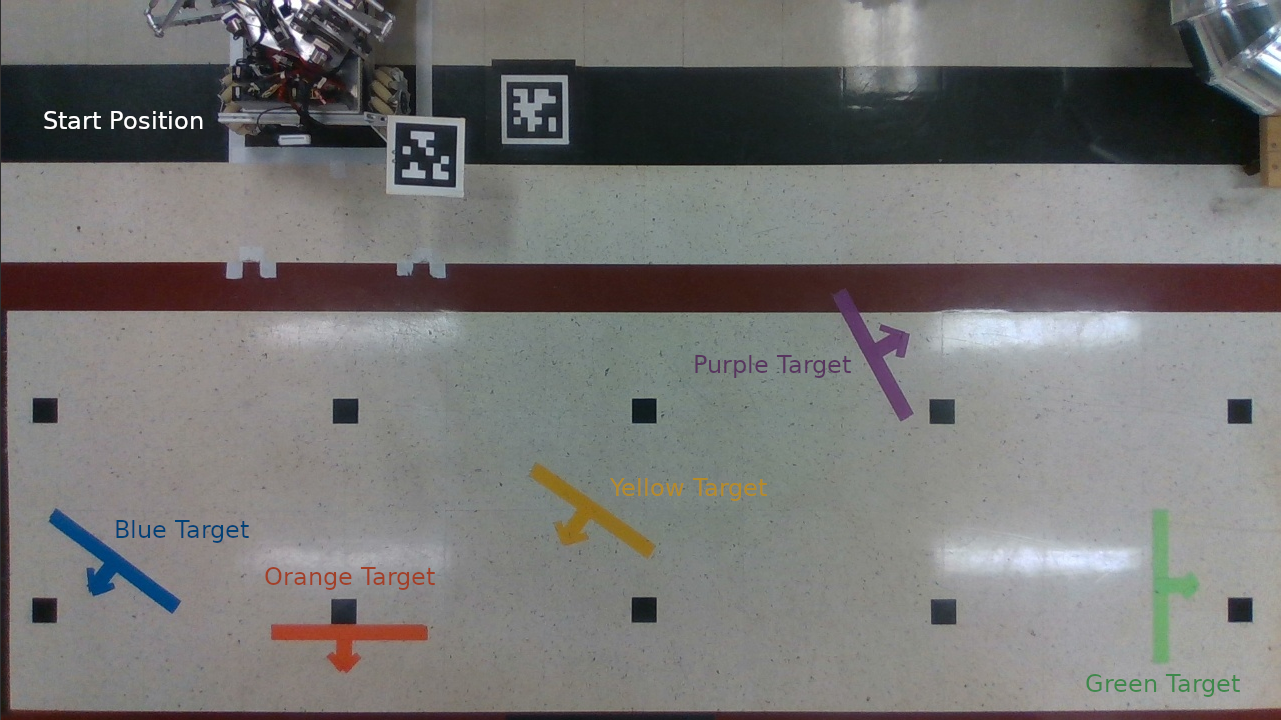

To collect human demonstration data, a simple task space was set up. This space included several differently-colored tape targets to indicate positions to which the human should guide an omnid.

The task space in which all testing was performed.

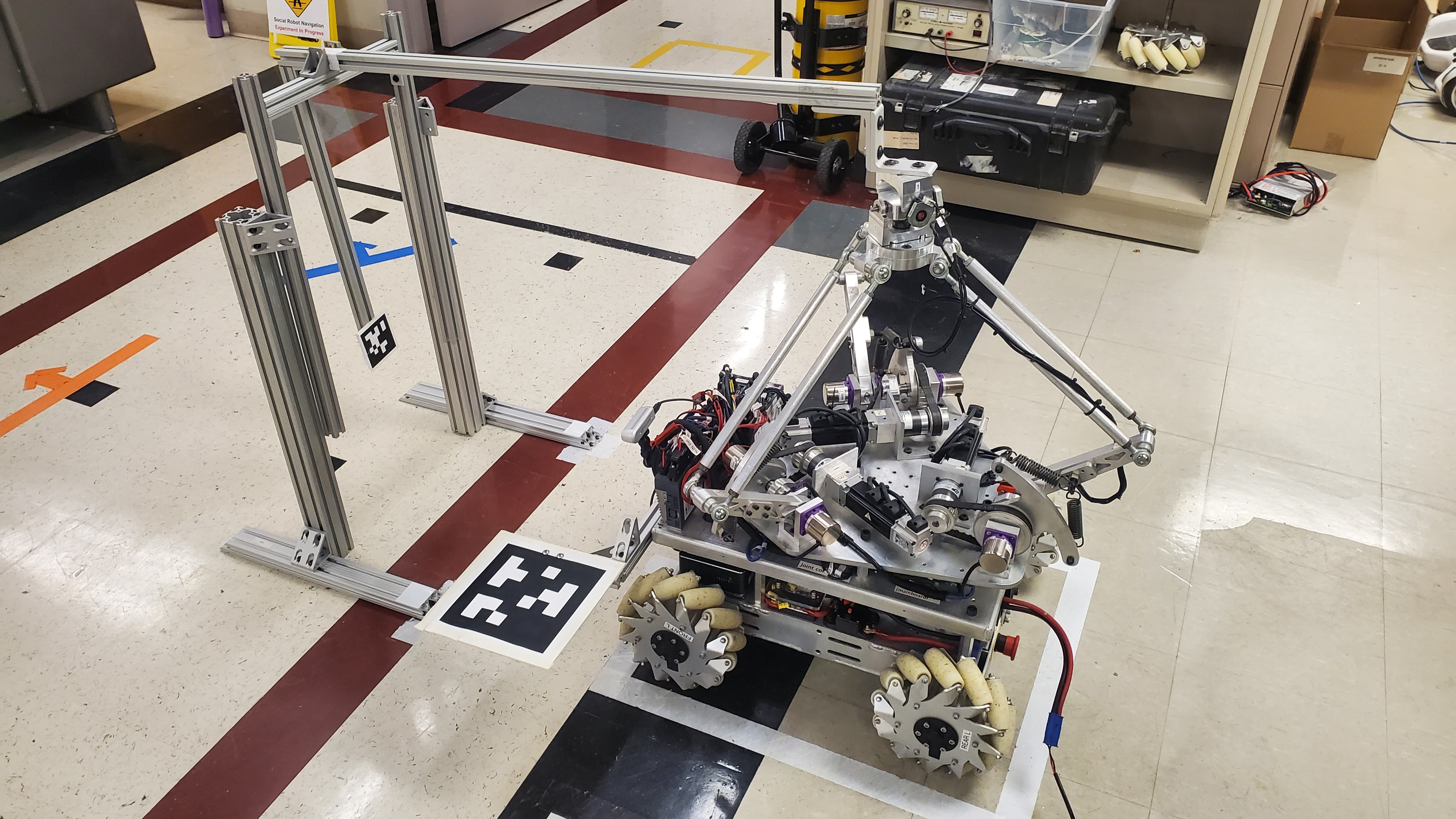

50 human demonstrations were collected for each target, by having the human drag an omnid by a small payload dubbed the “leash”. AprilTags are fixed to the floor, the robot, and the leash, allowing each to be tracked later for evaluation of any collected data. AprilTags detections are not passed as inputs to any models.

The “leash” - a small payload constructed of 80/20 with an AprilTag attached to it.

This rests on the “rack”, a rig used to home the Delta manipulator to a consistent position before every test.

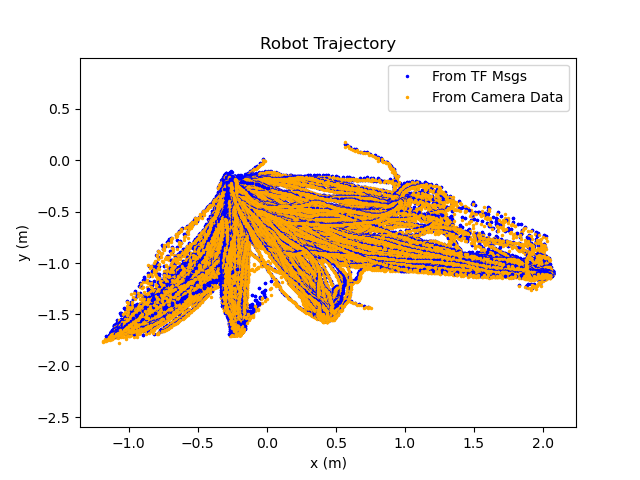

A plot showing the all trajectories followed by the robot in the training dataset.

Three cameras were used to collect image data - an overhead camera, a horizontal camera, and a camera onboard the omnid.

The camera feed from each camera during a run.

In order to record all this data, Hang-Yin and I wrote an omnid_data_collection package for ROS 2 Iron. This package included a node that recorded ROS bags based on configured input topics, launch files to start all required nodes, and bash helper scripts to guide users through the data collection process. The launch files relied heavily on the launch_remote_ssh package I wrote to launch all required nodes on multiple machines simultaneously.

This infrastructure was critical in collecting data quickly and allowed a full training human demonstration run to be recorded every 40 seconds.

Expand for a full list of data collected from runs.

This includes data that may only be meaningful on evaluation runs (with a generative model running).

- Overhead camera images/info

- Horizontal camera images/info

- Onboard camera images/info

- TF tree (for AprilTag transforms)

- AprilTag detections

- Joint states of all joints (including position, velocity, and effort)

- Commanded additional forces for EE force controller

- Commanded Delta motor velocity or torque

- Commanded base twist

- Payload’s reflected weight

- Estimated odometry

- Target positional achievement status

- Details of generative model used (if any)

Training

To train diffusion policy models, I forked the diffusion policy repository and set it up for use with omnid tasks.

Since the action prediction and receding horizon control used in diffusion policy relies on discrete timeframes of data, the ROS bag data had to be decimated at a certain rate. For models using image data, I chose this rate to be 15 Hz (one half of the camera refresh rate). For models not using image data, I chose this rate to be 50 Hz (one half of the joint state refresh rate). Data was decimated with a script that averaged collected data over the timeframe period.

For all the models I chose to use a neural network architecture based on the convolutional U-Net architecture, since the diffusion policy paper suggested that this may be sufficient for most tasks and easier to tune than the alternative transformer architecture.

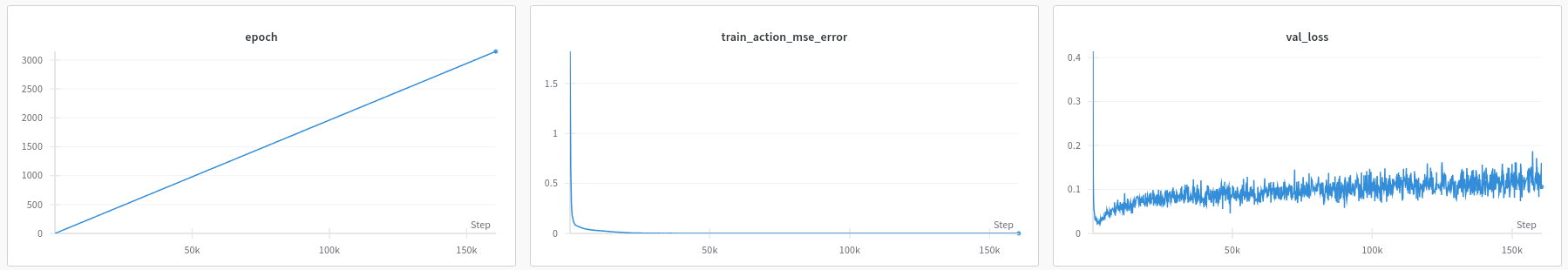

Training plots typically looked something like this, with validation loss quickly hitting a minimum and then rising steadily. Validation loss rising like this typically indicates overfitting. In the case of generative model like this one, however, overfitting may not lead to worse performance.

Expand for more detail on the code required to get this model training.

Luckily, the diffusion policy repository is generally well set up for quickly adding new tasks - but the cost of this flexibility is that the codebase structure takes some time to understand. In the end, since I was only creating new tasks, I could get it to work by simply adding new PyTorch dataset loaders, environment runners, and hydra task configurations. Finally, training data had to be converted from from ROS bag data to the zarr format expected as input to the training pipeline. Decimation occurred during this conversion.

Evaluation

Gauntlet Task

The gauntlet task was designed as a method of evaluating the diffusion policy models’ performance both in long, sweeping actions across the task space and in fine positioning at each target. Human collaborators would have to guide the omnid to every target in the task space in a set order. At each target, the human needs to precisely locate the omnid’s AprilTag at the target location (within a small radius), and hold the omnid there for a certain period. This precision location is confirmed by the overhead camera.

An example run of the gauntlet task.

The combined magnitude of the X/Y force components on the end effector are then calculated from the data. This force value and the time taken to complete the gauntlet are used as a metric to evalute the run performance.

Results

Architecture Selection

From the start, it was fairly easy to rule out some system architectures. For example, the position prediction architecture produced uncontrollable oscillation of the end-effector that prevented any precise positioning. This architecture may work with some further refinement (ex: output smoothing), but in its current state was infeasible.

Erratic oscillation experienced while running position prediction models.

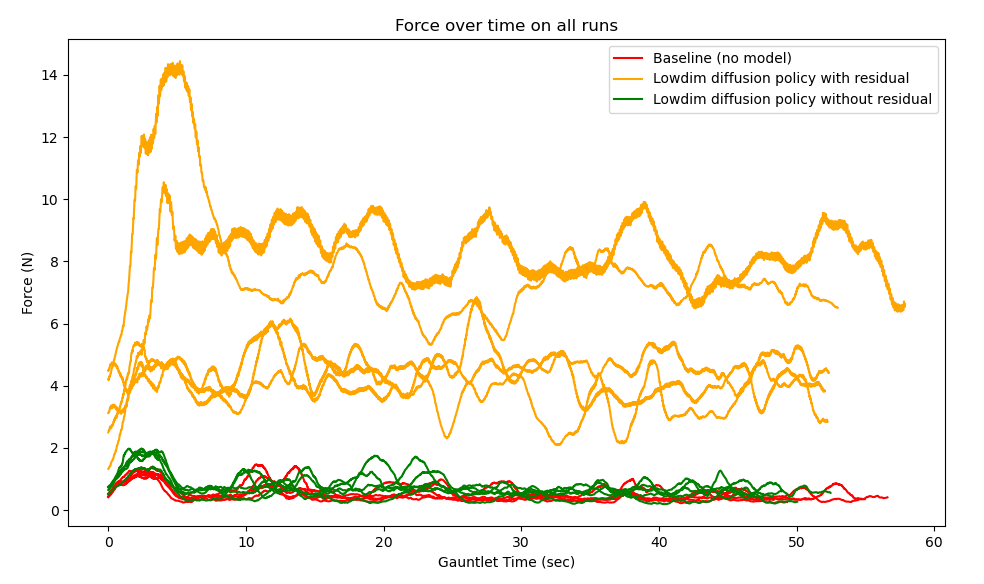

The force prediction architecture generally fared much better. Actions performed were subtle, but may help with precise positioning of the omnid. However, using force prediction with residuals performed poorly for some model configurations, also experiencing (less erratic) oscillations and increased force readings. This suggests that predictions did not necessarily line up well with the actual force feedback, and large components of that feedback was fed back into the force controller as additional force.

The force experienced at the end-effector is much higher for this lowdim model when using residuals.

The same model, without residuals, performs comparably to the baseline on this metric.

There was not sufficient time during the project to test the base twist prediction architecture, so it remains to be seen how that architecture will compare.

Model Performance

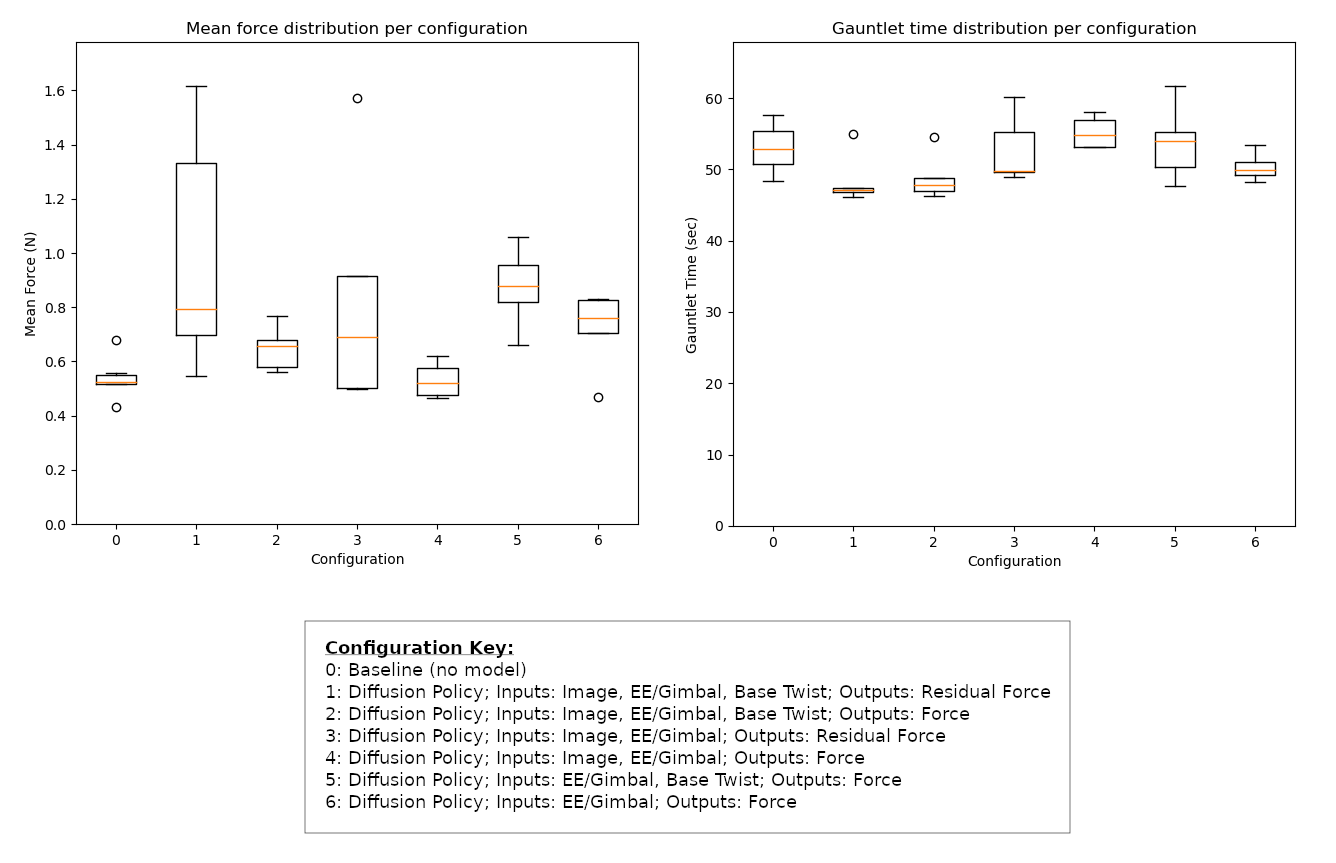

As mentioned, the force prediction architecture was the best performing architecture. Below is a plot of the effectiveness of a few permutations of that architecture on the gauntlet task from preliminary data.

It seems that using the diffusion policy model does not reduce the force experienced at the end effector. For all models, this force increased - although marginally. Where some improvement can be seen is in the completion time for the gauntlet. It would seem that the predictive actions taken by the model help the user precisely position the omnid more quickly in the target positions, thus decreasing the total gauntlet time. Some models show better performance, and generally the image models show better performance. However, one of the low dimensional models (6) appears to do pretty well, suggesting that for this task image data may not be necessary.

It is important to note that the improvement over the baseline is very slight. This is likely because the float controller that allows the user to position the base of the omnid under the payload already performs well. Improvements on this may only be incremental. But if more data and experimentation can show that performance consistently improves with diffusion policy models, this may be an avenue for improving the experience of human collaborators with these robots.

Future Work

While preliminary results from this testing show some promise, much work still needs to be done to explore the potential benefit of generative models like diffusion policy for assistive tasks with the omnid system.

1. Improved evaluation.

Task completion time and force experienced at the end effector may not be the best quantitative metrics by which to judge the effectiveness of assistive action prediction. They do not necessarily measure how easy it is for a human collaborator to work with the omnids. Developing better metrics may help make the effect of any particular model more clear.

Also, the gauntlet task also may not be effective as an evaluation of the assistive action prediction. Designing other tasks for evaluation (such as payload manipulation) may give better insight into model effectiveness.

2. Exploring other model architectures.

As mentioned, I trained all models with the U-Net diffusion policy architecture. As per the diffusion policy paper:

In general, we recommend starting with the CNN-based diffusion policy implementation as the first attempt at a new task. If performance is low due to task complexity or high-rate action changes, then the Time-series Diffusion Transformer formulation can be used to potentially improve performance at the cost of additional tuning.

This task, especially when performed with lowdim models, is certainly high-rate. So attempting to tune the transformer formulation could be an alternative to improve performance.

3. Exploring other system architectures.

The Northwestern omnid team opted to not try the base twist prediction architecture at the time of this project, as it may cause erratic behavior on the part of the omnids. This might be an interesting architecture to try. The prediction could be used directly, or as a residual (which would require some code modification for training), or some other blending method could be used to blend the float controller’s output with the model’s prediction output.

Some blending or smoothing method could also be used with the position prediction method to make it a feasible method as well.

While the force prediction method is currently the most successful, it’s also possible that it could be improved by using some smoothing or blending method to combine the model’s output with feedback.

4. Model tuning.

While I did try several different inputs and outputs, model parameters are also important to the performance of a model regardless of architecture. Some candidates for experimentation are:

- Length of observation horizon

- Length of prediction horizon

- Length of action horizon

- DDIM vs DDPM noise scheduling and noise scheduling parameters

- Data decimation rate

- Length of training (epochs)

5. Collecting more data.

As is typical in machine learning, the more (good) data, the better. Exploring the influence of more data on the effectiveness of the models may help determine how much data is “enough”.

6. Testing with the full three robot system.

Once reasonable results are obtained, it would be very interesting to test the full three robot payload manipulation with predictive models running for each robot. This would show if the assistive action prediction approach is effective beyond just the simple single robot case.

There’s certainly a lot more to explore in this research! The data collection infrastructure and machine learning pipeline developed during this project should make performing further assistive action prediction research on the omnid platform smooth.

Big thanks to Hang-Yin for working with me on developing this infrastructure and Matthew Elwin for advising the process.